SAMS news room

Baleen whales may sniff out their meals

Scientists investigating how baleen whales have become such effective feeders believe that the giant marine mammals may be able to sniff out the best opportunities - through their blowholes.

Baleen whales are a grouping that include blue, humpback and right whales and feed on huge quantities of zooplankton, such as krill and fish to maintain their bulk. Their ability to accurately locate an abundance of zooplankton in the vast ocean has puzzled scientists, but a team led by Dr Conor Ryan, Honorary Research Fellow at the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) in Oban, may have uncovered one of their secrets.

When zooplankton are grazing on microscopic plant-like phytoplankton, a chemical called dimethyl sulfide is released into the sea and then into the air. The scent from this chemical is already known to attract seabirds to a feeding frenzy. It may also be a signal to baleen whales too, which might be able to smell in stereo on account of having two nostrils (unlike dolphins which have a single nostril).

The findings highlight an urgent need for further research into whether the same feeding strategy is encouraging whales to ingest plastic debris. Fouling that grows on plastic floating at sea also emits dimethyl sulfide, which whales may mistakenly associate with food.

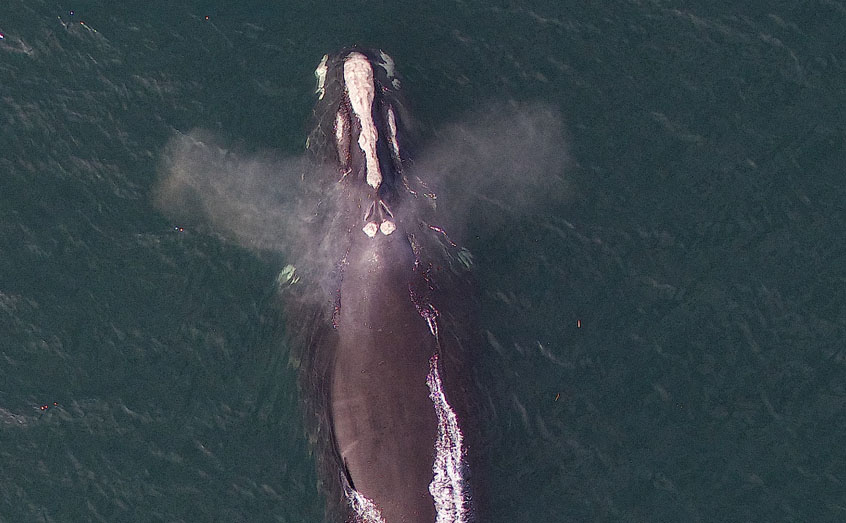

Dr Ryan collaborated with an international team of scientists working in every major ocean and used drone images of 14 different species of baleen whale to measure the spacing between the two nostrils on each blowhole. Their findings, published today [Wednesday] in Biology Letters, show that those whales with a preference for eating more zooplankton than fish, such as the northern right whale, have wider nostril spacing and are therefore better equipped to potentially sniff out the location of grazing zooplankton.

Dr Ryan said: “Whales have massive bodies, but how do they meet that huge demand for calories? The methods some use to feed, such as lunge-feeding, are also very energetically expensive, so they need to find high densities of prey to make eating worthwhile.

“Phytoplankton emit a gas as they’re being fed on by zooplankton - ‘the smell of the sea’ as we know it - and it is possible that the whales can detect this, a bit like how some birds are attracted by the smell from freshly cut grass.

“Whales that have their nostrils wider apart are better equipped to smell ‘in stereo’ and could potentially locate feeding opportunities by homing-in on the source of a smell.”

While the findings are not yet definitive proof that whales can smell, it is the first time the stark correlation between feeding preference and the distance between nostrils has been shown. Dr Ryan says the new discovery is a crucial step to discovering more about how whales find food, but also how they may fall foul to threats in their environment such as plastic debris.

Dr Ryan added: “If indeed whales do locate food by smelling dimethyl sulfide, there is a heightened risk of them eating plastic, because the fouling that grows on plastic floating at sea smells like plankton.

“This is why some seabirds cannot resist eating plastic and feeding it to their chicks. Understanding whales’ ability to smell could help us figure out why some species are so prone to plastic ingestion.”

The analysis was carried out in Scotland (SAMS and University of St Andrews) and Ireland (National University of Ireland, Galway) in collaboration with scientists based in the USA (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, University of Hawai’i, African Aquatic Conservation Fund, SR3 SeaLife Response, University of California, University of Wisconsin and Stanford University), Canada (Dalhousie University & LGL Ltd. Ontario), Mexico (Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur) and Falkland Islands (Falklands Conservation). Fieldwork was conducted in the Arctic, Indian, North Pacific, North Atlantic, South Atlantic and Southern Oceans.

For more on SAMS' marine mammal research, check out our #WhaleTalk campaign.